Image

James Bidgood, Pan, 1965, C-print, 22 x 22 in. Courtesy of ClampArt.

PAST

Classical Nudes and the Making of Queer History

Oct 17, 2014 - Jan 04, 2014

For over 2,500 years, the classical nude has been the dominant visual form for representing the human body in the Western world. Ironically, all that time, it has also been intertwined with the history of perhaps the least visible aspect of our self-representation—the history and iconography of same-sex desire. These nudes are in every sense of the term iconic; they are the building blocks of our Western visual culture.

For centuries, queer people have stared at classical nudes for secret signs that speak to them, of them. Figuratively creating spaces where men can touch other men—and women other women—the classical nude was inevitably connected to a vision of a classical past that endorsed, even celebrated same-sex desire. From the very first wide-scale recovery of that past in the Renaissance to the scholarly work of the great German classicist Johann Joachim Winckelmann to the present day, every time classical nudes have re-emerged into discourse or fashion, it is evidence of a changing historical understanding of same-sex desire.

One such shifting historical frame is clearly in evidence in the last part of the exhibition. Because of millennia of overt sexism, the vast majority of classical nudes of same-sex origin are male. It was not until the mid-to-late 19th century that female artists were allowed to professionally represent the human form and thus their own same-sex desire.

Our modern ideas about sexuality demand that we scour the past for evidence of notions about queerness that we can recognize and name as precedents, that we can call our foremothers and forefathers. Yet, paradoxically, in order to understand this past as in fact “the past,” it has to appear different from what we know today. The tradition of the classical nude answers this desire because it is both familiar and yet also historically distant. Our identity today finds itself mirrored in a classical past that is both stable and ever evolving—no surprise given that we invented that past in order to find ourselves within it.

Made possible in part with public funds from the Fund for Creative Communities, supported by New York State Council on the Arts and administered by Lower Manhattan Cultural Council.

Related

PAST

Chitra Ganesh: A city will share her secrets if you know how to ask

Oct 18, 2020 - Jun 01, 2022

more

PAST

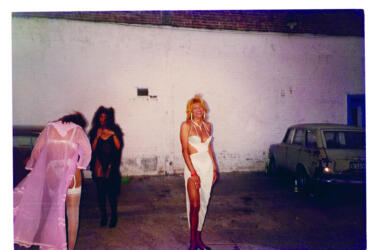

DARK RIDE: A Nocturnal Journey into the World of Erotic Desire

May 08, 2007 - Jun 30, 2007

more

PAST

SELDOM SEEN: Never or rarely seen works from the permanent collection

Nov 17, 2009 - Jan 23, 2010

more

PAST

LESBIANS SEEING LESBIANS: Building Community in Early Feminist Photography

Sep 14, 2011 - Dec 22, 2011

more

PAST

QUEERS IN EXILE: the Unforgotten Legacies of LGBTQ Homeless Youth

Jul 17, 2013 - Jul 28, 2013

more

PAST

Nude In Public: Sascha Schneider: Homoeroticism and the Male Form circa 1900

Sep 20, 2013 - Dec 08, 2013

more

PAST

INTERFACE: Queer Artists Forming Communities through Social Media

May 15, 2015 - Aug 02, 2015

more

PAST

MEDIUM OF DESIRE: An International Anthology of Photography and Video

Dec 18, 2016 - Mar 27, 2016

more

PAST

RUBBISH AND DREAMS: The Genderqueer Performance Art of Stephen Varble

Sep 29, 2018 - Jan 27, 2019

more

PAST

ROBERT GIARD (1939-2002) Particular Voices: Portraits of Gay & Lesbian Writers

Apr 25, 2018 - May 20, 2020

more