Image

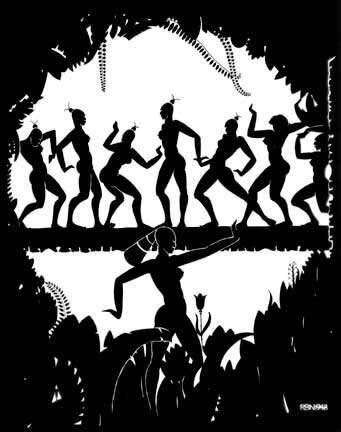

RICHARD BRUCE NUGENT Untitled, 1948 Ink on paper 24 x 18.5" The collection of Thomas H. Wirth

PAST

RICHARD BRUCE NUGENT: Harlem Butterfly

Nov 07, 2006 - Dec 21, 2006

Richard Bruce Nugent—Harlem Butterfly

by Thomas H. Wirth

from THE ARCHIVE: No. 21: Autumn 2006

Richard Bruce Nugent was a phenomenon who was not supposed to exist—an African-American artist influenced by Michelangelo, Beardsley, and Erte who devoured the novels of Firbank and Huysmans and wrote stream-of-consciousness prose—a black man trespassing in white Elysian fields.

Nugent was born in 1906 to a family of modest means but impeccable position in Washington, D.C.’s café-au-lait society. After the death of his father in 1920, his mother moved to New York, where he joined her a few months later. Handsome, intelligent, charming, and young, he soon found his way from West 18th Street, where they lived, to Greenwich Village.

He held a succession of jobs, ranging from bellhop at the Martha Washington Hotel to apprentice with the catalog house of Stone, Van Dresser, where he received his first training in art. Eventually he announced to his mother that he was going to be an artist and would not take another job—whereupon she sent him back to Washington to live with his grandparents.

There he became a favorite of the middle-aged poet Georgia Douglas Johnson. In June, 1925, at one of her famous salons he met Langston Hughes; Hughes’s first book, The Weary Blues, would be published by Alfred A. Knopf a few months later. Alain Locke, a Rhodes scholar and Howard University professor whose mother was a good friend of Nugent’s grandmother, also attended the salons frequently. He included Nugent’s story “Sahdji” in The New Negro in 1925. This anthology was the cornerstone of the “New Negro Movement”—now better known as the Harlem Renaissance.

Hughes wrote the then-famous gay novelist Carl Van Vechten about meeting Nugent: “I’ve met a couple of interesting fellows about my own age,—one a pianist and the other an artist, and we have been amusing ourselves going downtown to the white theatres ‘passing’ for South Americans, and walking up Fourteenth Street barefooted on warm evenings for the express purpose of shocking the natives.” Hughes rescued Nugent’s first poem, Shadow, from the wastebasket and sent it to Opportunity, where it was published in October, 1925, and created quite a stir.

Silhouette

On the face of the moon

Am I.

A dark shadow in the light.

A silhouette am I

On the face of the moon

Lacking color

Or vivid brightness

But defined all the clearer

Because

I am dark,

Black on the face of the moon.

A shadow am I

Growing in the light,

Not understood as is the day,

But more easily seen

Because

I am a shadow in the light.

Most readers believed that the poem was about race, but in a 1983 interview, Nugent explained that, “I intended it to be a soul-searching poem of another kind of lonesomeness, not the lonesomeness of being racially stigmatized, but otherwise stigmatized. You see, I am a homosexual.”

In August, 1925, Nugent accompanied Hughes on a trip to New York, where Hughes introduced him to Carl Van Vechten, Countee Cullen, and other Harlem Renaissance luminaries. Nugent decided he had had enough of Washington and returned to New York before the year was out, where he quickly followed up on Hughes’s introductions. Soon he saw one of his drawings published on the cover of Opportunity, met and moved in with Wallace Thurman, joined Jean Toomer’s Harlem Gurdjieff group, and joined with Wallace Thurman, Langston Hughes, Aaron Douglas, Zora Neale Hurston, Gwendolyn Bennett, and John P. Davis to publish the premier issue of FIRE!!—which they hoped would become the first African-American “art quarterly.” FIRE!! was the younger generation’s declaration of independence from the older black intelligentsia’s expectation that they would respectably represent the race.

Although it lasted only one issue (for financial reasons), FIRE!! was one of the most brilliant achievements of the Harlem Renaissance. It was a cooperative venture, free from the restraints imposed by the need to please patrons and publishers (who tended to be white), and independent of sponsoring organizations with “larger” political and social objectives. Aaron Douglas did the cover, decorations, and three wonderful, whimsical line drawings which are unlike any of his other work. Nugent, writing under the name of “Richard Bruce,” contributed two brush-and-ink drawings and Smoke, Lilies, and Jade,which Hughes discreetly characterized as “a green and purple story in the Oscar Wilde tradition.” It was, in fact, the first literary work on an openly homosexual theme to be published by an African-American writer.

A crucial element in Bruce Nugent’s social success was his striking persona. He was a brilliant conversationalist, specializing in charm and shock. A true bohemian, he often had no place to sleep. Despite a thoroughly masculine, if theatrical, demeanor, Nugent projected in conversation a flagrantly ambiguous sexuality. He made no secret of his erotic interest in men.

Soon after the publication of FIRE!!, Nugent moved with Thurman to the infamous “Niggeratti Manor” on West 136th Street, the setting for Thurman’s roman à clef about the Harlem Renaissance, Infants of the Spring, in which Nugent appears as a major character, Paul Arbian. “Niggeratti” was the appellation Thurman invented for the group of young, adventurous, and relatively unconventional Harlem intellectuals to which he and Nugent belonged. In the novel, Arbian/Nugent is an artist who “indolently” creates “voluptuous geometric designs” and “erotic drawings” that “are nothing but highly colored phalli.”

Nugent worked closely with Aaron Douglas, accompanying him to lessons with his mentor Winold Reiss and helping him execute murals on the walls of basement cabarets. Nugent reported that some of these were executed in two colors—red and blue. When they were viewed under blue light, the African past was visible; under red light, the scene shifted to the modern city.

Silhouettes in brush and ink such as those in FIRE!! and the illustration accompanying this article are an important segment of Nugent’s oeuvre. Four such pieces on a mulatto theme appeared in Charles S. Johnson’s important anthology, Ebony and Topaz (1927). Numerous others, mostly unattributed, appeared throughout the late 1920s and early 30s in Opportunity, the monthly magazine of the National Urban League. The influence of Aaron Douglas is evident, but Douglas’s comparable work is sober, often heroic in its subject matter, incorporating regular arcs and straight lines rather than Nugent’s S-curves. Nugent’s figures move; the dance is one of his favorite themes. He illustrated an article by Wallace Thurman on jazz dance that appeared in the May 1928 issue of Dance magazine.

Line drawings, executed in pen and ink or pencil, are an important aspect of Nugent’s work. In other drawings he experimented extensively with color, using Japanese dyes, which were normally used to color photographs. In 1930 he executed the “Salome Series” incorporating biblical themes in which unexpected juxtapositions of colors, strongly idiosyncratic stylistic elements, and unconventional composition emphasizing the borders rather than the center combine to stunning effect.

Throughout his working life, Nugent has been legendary for his erotic art-deco drawings. These show the strong influence of Beardsley and Erte, but the style is distinctly Nugent’s. Eroticism is an element in nearly all of Nugent’s work. But “erotic” must be sharply distinguished from “pornographic.” With their elegant style and exquisite colors, even the most explicit of Nugent’s drawings are simply too beautiful to arouse the viewer sexually.

Nugent also worked in oil and pastel. His oils are more “serious” than his graphics, with his distinctive stylistic qualities less in evidence. Nonetheless, they effectively express his endless fascination with men.

Nugent was persistently unconventional in both his life and his work. He refused to pursue a “career.” He did not permit others to impose on him their definitions of who he ought to be, either as an artist, an African-American, or a “man.” He insisted on freedom when freedom was not allowed.

This landmark retrospective at the Leslie-Lohman Gallery is Nugent’s first one-man show in New York and the first exhibition of his work to include his sexually explicit images.