Image

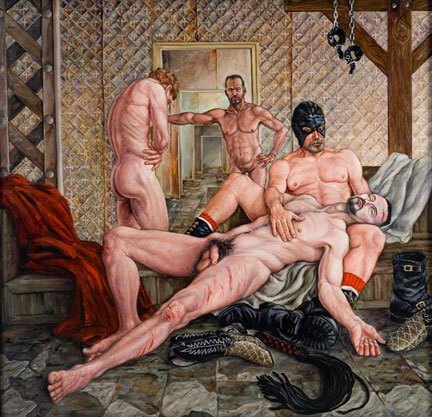

DELMAS HOWE he Gentle Executioner, 1997 Oil on canvas 54" x 54" Collection of Leslie/Lohman Gift of the artist

PAST

STATIONS: A GAY PASSION

Mar 18, 2007 - Apr 21, 2007

COLORING THE WORLD QUEER DELMAS HOWE’S STATIONS: A GAY PASSION

By Lester Strong

From THE ARCHIVE: No. 22: Winter 2007

Delmas Howe has described his Stations: A Gay Passion as both a celebration and a memorial. With titles like The Stripping, The Flagellation, and Veronica’s Kiss, the eighteen paintings in the series clearly refer to the Christian Stations of the Cross—”but only loosely,” Howe told me in one interview about the paintings. “I’m not portraying Christ or his passion. I’m portraying our own gay passion that has centered for so long now around the disaster known as AIDS.”

Set in the 1970s and early 1980s on the gay sex piers of New York City’s Greenwich Village, the series not only portrays the celebration by gay men of their sexuality at the height of the “gay liberation” movement, but also memorializes the many gay men lost to AIDS in the decades that have followed. In Howe’s own words: “The sex piers are gone now. But the paintings are intended to evoke a conglomeration of feelings: the celebration of sexuality and the male body that the sex piers represented, the thrill of all that sex so openly available at the time, and of course the grief that has followed with AIDS.”

Howe speaks from a personal knowledge of both the sex piers and AIDS. Although a native of Truth or Consequences, New Mexico—a small town located in the southern part of the state that’s known mainly for its distinctive name, which it adopted in the early 1950s at the urging of a well-known television show of the era looking for a way to promote its image nationally—he lived in New York from the early 1960s until the late 1970s, when he moved back west first to Texas, then to his hometown so he could care for his aging parents. In New York, he studied at both the School of Visual Arts and the Art Students League and began his art career, but he was no stranger to the sex piers once they became a prominent part of the city’s gay male life. “Those piers were the scene of some pretty amazing goings-on,” according to Howe. “It was a passionate experience for the men who participated, where we celebrated our new-found freedom after Stonewall. Unfortunately, it was a celebration that started and ended within a decade because AIDS intervened. Most of the men I knew from those days are all dead now.”

It wasn’t just friends who died, though. “In 1990, my partner Mackenzie Pope became very sick,” Howe said. “There was a gay doctor in Truth or Consequences who had trained in the AIDS wing of a large New York hospital, and the local public health nurse was very helpful. But at the time there was no supportive network for people with AIDS in southern New Mexico, so we had a struggle caring for Mackenzie until he died in 1993.

“I was amazed at the grief I felt,” Howe continued. “I didn’t know how intense an emotion it is, or how it makes you so conscious of the moment. The loss of Mackenzie, the loss of so many friends.” He knew he wanted to commemorate all the losses in his art, but it wasn’t until a few years later that the idea for Stations emerged.

“I went on an extended tour of Europe,” Howe explained, “a kind of pilgrimage, studying first-hand many of its art masterpieces. I visited church after church after church, and found that Christian art, when you really pay attention to it, is amazing for its homoerotic content, much of it S&M homoerotic art. The passion and crucifixion of Christ, the martyrs—all that tortured flesh, a lot of it male, just cascading down from every direction. It occurred to me that I’d come across that in my life in New York, in the S&M scene with its costumes and role-playing. Sometime after that, I was in New York again, and made another pilgrimage through the old gay haunts that are now mostly gone—the piers, the trucks, the bars of Greenwich Village. That’s when it all came together. I decided to do a Gay Passion, set on the sex piers, commemorating the tens of thousands of wonderful, attractive, intelligent men wiped out because they were celebrating their sexuality. I also decided to use S&M imagery to emphasize the torture that AIDS has caused the whole gay community.”

Anyone familiar with Howe’s art knows that much of it embodies an erotic intensity which speaks to the heart of contemporary gay male sensibility. The male physique is not his only artistic interest, but the sexual vitality of the men he does portray—whether naked or clothed—is never in question. His Rodeo Pantheon series, for example, recasts American cowboy art in terms of an underlying homoerotic content that would have scandalized Frederic Remington. His Stations series, as already noted, points directly to the homoerotic S&M motifs suffused through much Christian art and hagiography. And some of his most recent work, a series of cowboy angels, hints at a heaven where the main criterion for entrance, in regard to men at any rate, seems to be an impressive pectoral development and washboard stomach.

Because of this erotic slant, Howe’s work has often been marginalized as “queer art” of interest mainly to gay men, and because of what might be called its figurative realism, it has sometimes been dismissed as a throwback to a kind of second-rate academic art. Figurative though it may be, however, his art is hardly academic, and much of its apparent realism is more in the eyes of the beholder than in the paintings themselves. Take a close look at the work, and live with it for a while. Howe’s art has a way of entering your psyche and molding it in new ways. A close encounter with his Rodeo Pantheon—which preceded the “gay cowboy” movie Brokeback Mountain by well over a decade—subverts a tired genre of American painting in a way that may well permanently change the way you think about cowboys and rodeos. The subdued colors of the Stations series perfectly capture a sexuality as stripped of its romantic trappings as it was in the obsessive pursuit of sex by many gay men during the 1970s. The grays, the blacks, the leather masks and whips also foreshadow a world in which every sexual act becomes a tortured signifier of possible illness and death.

In an introductory essay to Rodeo Pantheon, a 1993 monograph on Howe’s series published by Éditions Aubrey Walter, British photographer and art historian Edward Lucie-Smith wrote that Howe’s art “belongs to a new species of polemical avant-garde art.” It’s not hard to see why. Like feminist art, or work by racial and ethnic minority artists, it demands that the viewer take a step back from accepted social and intellectual assumptions and view the world from a different perspective. There’s nothing particularly innovative in the materials or method of Howe’s art: no stuffed Angora goats with tires around their middles à la Robert Rauschenberg or dead tiger sharks floating in tanks of preservative fluid à la Damien Hirst, no revisions of photographic images via silkscreen or other media à la Andy Warhol. But given time and a viewing eye open to new ways of perceiving, his always painterly art can work its own kind of magic and color the world vibrantly queer.

Note: Charles Leslie and Fritz Lohman are two of Howe’s New York friends from the 1960s and 1970s who survived the killing fields of AIDS. It’s thanks to their continuing friendship with and support of Delmas Howe over the years that Stations: A Gay Passion makes its East Coast debut March 13–April 21, 2007, at Leslie/ Lohman Gay Art Foundation.

Lester Strong is Special Projects Editor for A&U magazine. Articles by Strong have also appeared in The Gay and Lesbian Review, Out magazine, The International Journal of Sexuality and Gender Studies, and The Journal of Homosexuality, among other publications.